Sign Theory Intro

Contents...

Theory of Signs I

In this post we’ll talk about extending the notions of signs. Typically, we see signs as positive $(+)$ and negative $(-)$ and have the relation:

\[a + (-a) = 0\]That is, the signs cancel. This is all known as true, we understand it well and it makes sense. Like with magnets or electricity, intuitive and easy to learn.

More than 2 signs, Let’s try 3

But, what if there are more than 2 signs? How about 3? We’ll call it $\ast$. How would we reason about them? Well, one way we can achieve the canceling would be with the relation

\[a^+ + a^- + a^\ast = 0\]where $a$ is any number. We’ll call it the basic axiom of signs. This let’s us do arithmetic with them.

For now, let’s just consider $a$ as a real number, like $4$ or $-3.23$. We can write as numbers

\[1^\ast \quad (3.2)^+ \quad (-\pi)^- \quad 1^\ast + 2^-\]and so on.

How do we Multiply and Divide?

To have a logically sound theory, we will define the multiplication and division rules for the signs follows:

Multiplication: There are various ways to define multiplication. I will share the easiest one to learn:

\[\begin{array}{|l|*{l}|{l}|} \hline \times & + & - & * \\ \hline + & + & - & * \\ \hline - & - & * & + \\ \hline * & * & + & - \\ \hline \end{array}\]Division: Similarly from the definition of multiplication we may obtain a sign table for division (these come in handy when doing computations as they are not as natural as our definitions of regular signed theory).

\[\begin{array}{|l|*{l}|{l}|} \hline / & + & - & *\\ \hline + & + & * & - \\ \hline - & - & + & * \\ \hline * & * & - & + \\ \hline \end{array}\]For example, we could have

\[2^\ast \times 3^+ = 6^\ast \qquad 3^- \times 8^- = 24^\ast \\ \frac{3^\ast}{6^-} = \frac{1}{2}^{-}\]What about negatives inside the signs?

What if we have something like $(-2)^+$, how to interpret that? Well, one way to make the geometry sound would be as follows, using the postulate:

Postulate (Existence of Interpolated signs within sign wrappings): A number is said to be interpolated when its inner sign wrapping opposite is taken. For example, the interpolation of $6^\ast$ is $(-6)^\ast$ since the inner sign wrapping ($+$ and $-$) is changed to its opposite. Let there be postulated numbers that are of opposite directions within their sign wrappings, that is let there be numbers of the kind $(-1)^\ast$ that also yields $0$ when added to its additive inverse. Thus, $(-1)^\ast + 1^\ast = 0.$

Using this, we can relate the negatives inside the sign top signs with the other numbers.

Relation of negatives in all sign wrappings: For all $a \in \mathbb{C}$ we have \((-a)^+ = a^- + a^*\) \((-a)^- = a^+ + a^*\) \((-a)^* = a^+ + a^-\)

Proof. Consider the following construction, by the law of reflexivity we have

\[a^+ + a^- = a^+ + a^-\]We also know by interpolated signs that $(-a)^+ + (-a)^- + (-a)^* = 0$, so adding $0$ to the right in the equation above gives

\[a^+ + a^- = a^+ + a^- + \left[(-a)^+ + (-a)^- + (-a)^*\right]\]with some pairing this turns the right hand side into

\[[a^+ + (-a)^+] + [a^- + (-a)^-] + (-a)^*\]and using the definition of additive inverse we may simplify the right hand side into

\[0 + 0 + (-a)^* = (-a)^*\]Putting all of this together we obtain the left hand side equals the simplified right hand side, or:

\[a^+ + a^- = (-a)^*\]The other forms of this statement may be obtained by multiplying $1^*$ or $1^-$ on both sides of equation above, giving all three identities, as desired. $\blacksquare$

Looking Geometrically

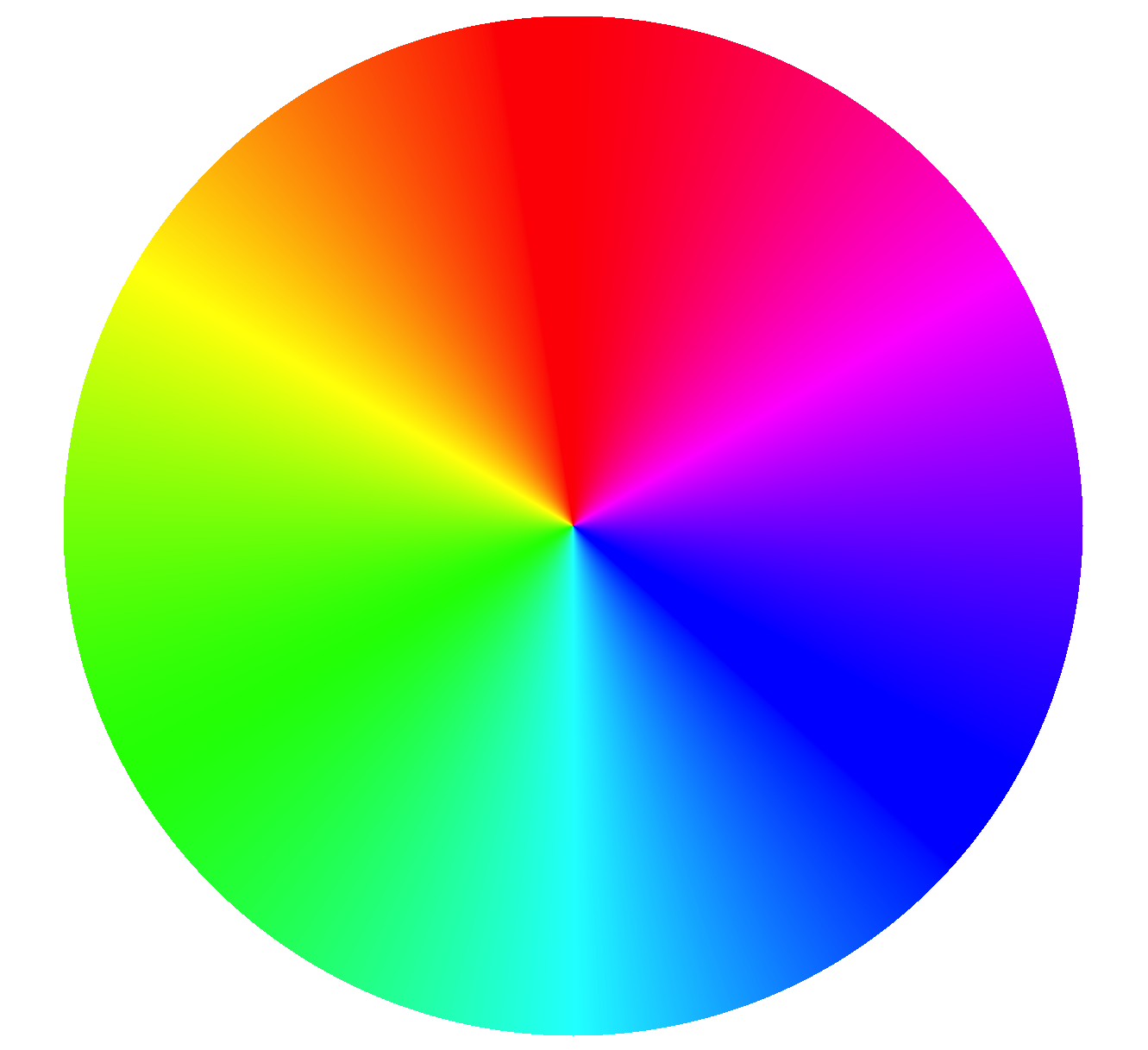

Sounds a little weird, right? All of this? Too many signs around? It gets more interesting and easier when we add some geometry. The numbers we are describing all lie on a circle with 3 axes. We can see them the best as a color circle given below:

1: A color circle

1: A color circle

The positive $(+)$ axis is red, negative axis $(-)$ is green, and auxiliary axis $(\ast)$ is blue. They all intersect at the origin! Numbers are written on this circle as colors. For example, $1^+ + 2^\ast$ looks like magenta. And $(-2)^+$ is the sum of blue and green or 2 units backwards along the red axis; this gives cyan for $(-2)^+$. Are we really adding and doing math with light? It just might be so!

Wrapping up…

We showed the basic idea of sign theory and how to do arithmetic with the sign numbers. It turns out that doing arithmetic is like changing colors of light!

$\#/.$